Today, let’s explore the captivating world of yamato-e, an artistic style that emerged during Japan’s Heian period (794-1185). It’s a journey through time, exploring the evolution of Japanese painting and its distinctive departure from Chinese influences.

-

The Emergence of the Yamato-e Style

1.1. Differences between Yamato-e and Kara-e:

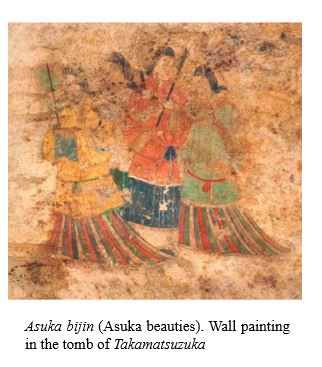

At the dawn of the Heian period, Japanese painting bore the unmistakable imprint of Chinese art, characterized by vibrant colours and sharply delineated figures. This influence can be traced back to the Nara period (710-794) and was evident in murals like those found in the Takamatsuzuka tomb. However, as Japan’s ties with China waned, a shift occurred, leading to the rise of a uniquely Japanese style known as yamato-e.

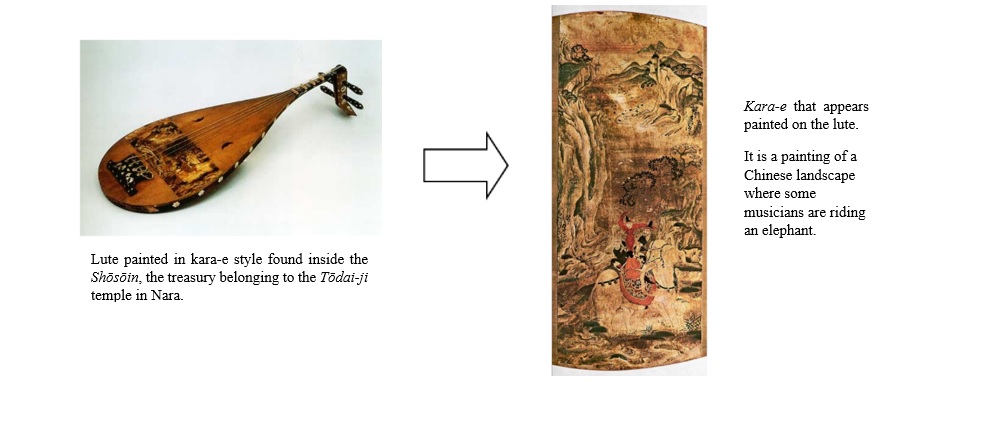

Yamato-e, which translates to “Japanese painting,” began to diverge from the prevailing Chinese-influenced style, known as kara-e. While kara-e favoured grand landscapes and intricate details, yamato-e embraced scenes of everyday life and Japanese themes. This marked the beginning of a new era in Japanese art, characterized by a focus on indigenous subjects and a departure from Chinese conventions.

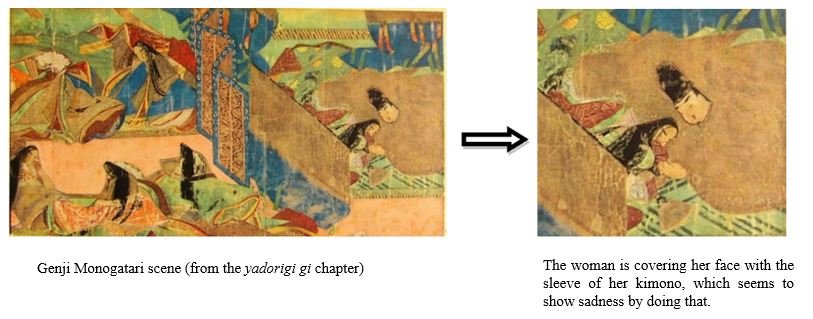

In kara-e, as can be seen in the image above, apart from the striking colors, people were usually depicted small in comparison to the immense landscapes and rugged cliffs. However, in yamato-e, more mundane and everyday situations can be observed. The focus shifts from landscapes and imposing cliffs to scenes of courtly life or the depiction of a popular Japanese folk tale narrative.

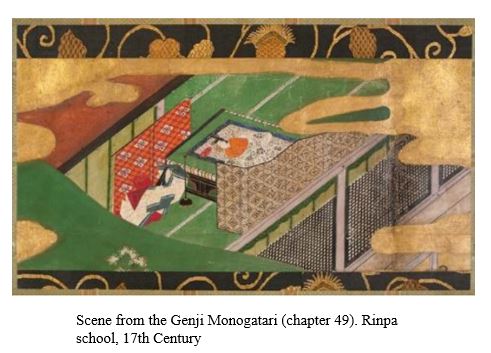

As can be seen in the image, the landscape ceases to be the main element and becomes a simple background used for decoration. Here, people become more important, contrasting with the more influenced Chinese paintings, where the focal point was the landscape. Clouds were used to separate space, also giving a sense of perspective where it seems that the viewer is a kind of “higher being” looking on everyday situations and people’s daily lives.

1.2. Waka

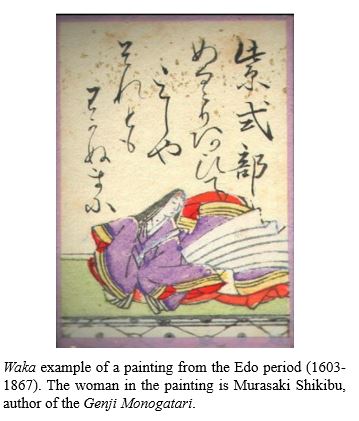

Waka is a form of poetry that deals with emotional themes or nature, reflecting people’s feelings. This type of poetry was oral in nature and was considered women’s poetry, as opposed to kanshi, which was written in Chinese, and not intended to be sung. However, with the fall of the Tang dynasty (618–907) and the Japanese growing awareness to appreciate their own culture a little bit more, waka began to be used increasingly, and was even sponsored by the emperor with the first anthology of poems known as Kokinshū, dating back to the year 905.

This type of poetry would establish itself as the quintessential poetic genre. Waka and yamato-e were also used together at that time by the known uta-e, which could be described as an illustrated poem. This type of poem was typically written above or on one side of the painting. However, it was with the emakimono where yamato-e became even more renowned, and it is thanks to preserved illustrations from works, like the one by Murasaki Shikibu, that helped us understand this style even better.

1.3. Emakimono

Since women were unable to leave the court and had a very limited idea of the outside world, a feminine literature began to emerge, where stories were told about daily life at court, or about romances that were, in many cases, idealized. This type of writing style made used of hiragana, and also combined narratives full of feelings and sensitivity. It was known as yamato kotoba or onnade, while the masculine style was known as kanbun, or otokode.

Murasaki Shikibu, the author of the Genji Monogatari, fulfilled all of these onnde style characteristics. These writings, moreover, appeared in a very particular format known as emakimono, or what it would be an illustrated scroll. This format combines, as its name indicates, illustrations accompanying the text, making the reading more graphic by having a drawn representation of what the text says. They were composed of sheets of paper or silk joined horizontally and rolled onto a spindle.

-

Genji Monogatari Emaki

The tale of Genji follows the characteristics of what it was considered the feminine literature of the time. It narrates the amorous adventures of the prince with the ladies of the court. This prince, named Genji, is the son of the emperor and a low ranked concubine. Genji, who ends up falling in love with his stepmother because she resembled his own mother, is exiled upon having a child from that relationship (as it was the greatest disgrace of the time). From then on, he will live a series of romances with different women, and it will be one of his sons who manages to become emperor.

When Murasaki Shikibu wrote the Genji Monogatari, it had no paintings associated with the story. It was in the early 12th century when the Genji Monogatari emaki began to be produced, that is, the tale of Genji in scroll form, with paintings associated with the text.

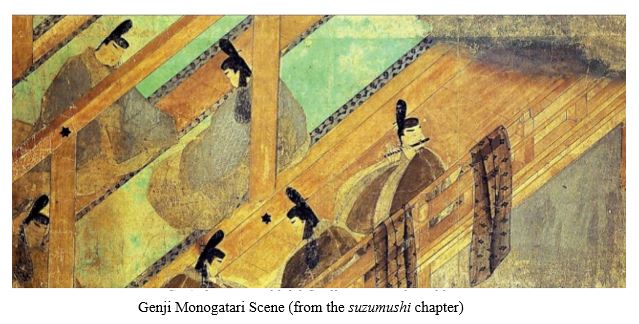

It is considered one of the oldest works reflecting the yamato-e style. However, very little of this emakimono is preserved today. Normally, in the emakimono, the painting and the text were done separately and then joined together by placing them side by side. In the Genki Monogatari emaki, both painting and writing have the same relevance.

2.1. Characteristics of the Yamato-e Style/Emaki:

Yamato-e paintings, particularly evident in emakimono, showcased distinctive features:

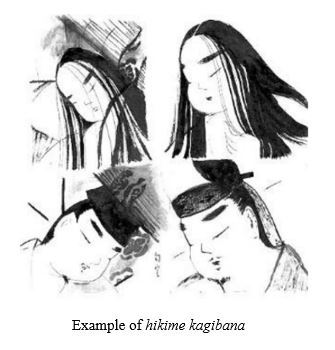

- Hikime Kagibana Technique: characters were depicted with slit eyes, hooked noses, and minimal facial expressions, reflecting a stylized aesthetic.

Despite making the characters lack facial expressions and all look alike by using this style, there is nevertheless a slight and subtle attempt to show emotions. This was achieved, for example, with the slight tilting of the characters’ heads, or the partial covering of their faces with the kimono sleeve.

• Fukinuki Yatai: Indoor scenes were depicted without roofs, providing a bird’s-eye view and enhancing narrative clarity.

• Tsukuri-e Process: Paintings were meticulously crafted using ink outlines, followed by colour application and detail enhancement, exemplifying the yamato-e technique.

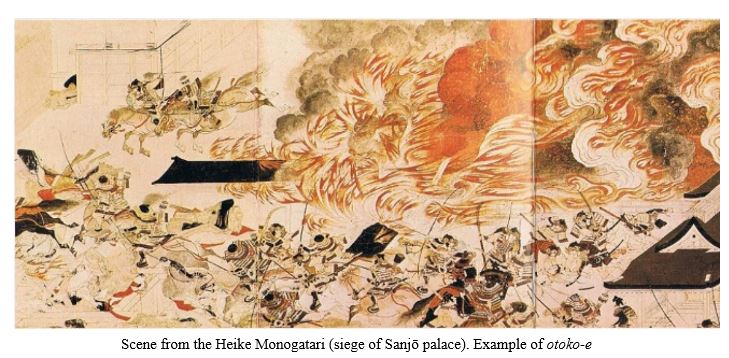

- It is possible to distinguish between a feminine painting style (onna-e) and a masculine one (otoko-e). An example of the onna-e style is the Genji Monogatari emaki, as it deals with court life and romance. The otoko-e style, on the other hand, would reflect warlike situations. The Heike Monogatari emaki (early 13th century) could be considered an example of this style. Its plot recounts the last years of the Heian period, where the fall of the Fujiwara clan led to the emergence of a much more austere society and the seizure of power by the samurai class.

-

Yamato-e in Later Periods

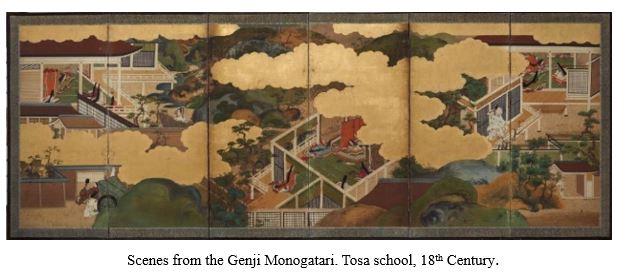

The yamato-e painting style, however, gradually faded into obscurity after the Heian period. Nevertheless, it is with the Tosa school, founded during the Muromachi period (1333-1573), and subsequently the Rinpa school belonging to the Tokugawa period (1603–1867), where yamato-e regains importance.

Initially, the Tosa school focused on themes from the Genji Monogatari. Later on, it also began to include paintings of flowers and birds.

The Rinpa school also revives yamato-e, both in theme and style. However, new elements from Muromachi or Momoyama periods (1568-1615) are added, giving a new touch to the classic yamato-e style.

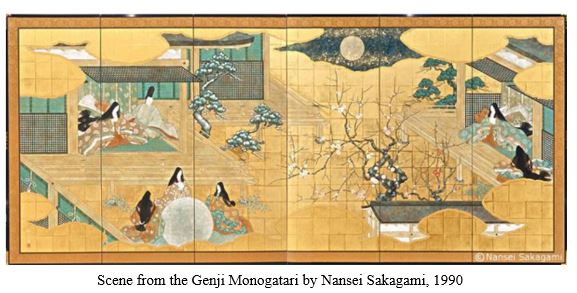

In most recent times, we can also find artists who continue to paint in yamato-e, or those who even recreate scenes from the Genji Monogatari.

-

Conclusion: Celebrating Japan’s Artistic Heritage

The emergence of yamato-e during the Heian period marked a transformative moment in Japanese art history, signalling a departure from Chinese influences and a celebration of Japanese themes and narratives. Through its diverse themes and storytelling techniques, yamato-e offered a window into Japanese life, culture, and aesthetics, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of Japanese art. As we reflect on its legacy, it’s evident that yamato-e continues to inspire and captivate audiences, bridging the past with the present in a timeless celebration of Japanese artistic heritage.